By Sen. Dan Laughlin (R-49)

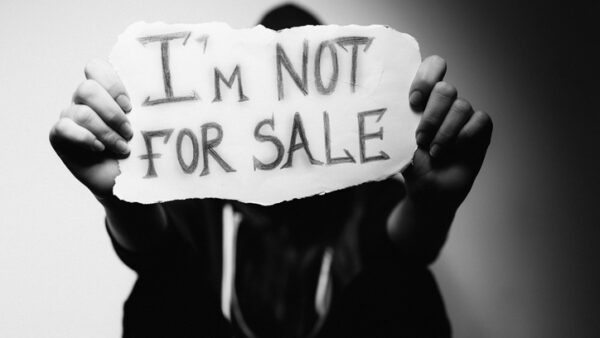

Your television is flooded with reports of sex trafficking rings on private islands, but the grim reality is there’s human trafficking happening down your street. January is Human Trafficking Awareness Month and although it would be easier to ignore it, human trafficking is very real and close to home.

According to the Department of Homeland Security, human trafficking is defined as the use of force, fraud or coercion to obtain some type of labor or sex act. Labor trafficking is the number one type of trafficking internationally, but sex trafficking is first in the United States.

Trafficking in Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania has the ninth highest number of reported cases, according to the National Human Trafficking Hotline. In the last five years, 1,096 human-trafficking offenses were charged in Pennsylvania — and those are just the ones that were caught. Many aren’t. Pennsylvania’s interstate system makes it easier to traffic victims, especially with our state bordering New York and New Jersey.

The hotline offers some insights into the victims, based on the calls they get. About three-quarters of the victims are adults, one-quarter minors. Almost all are women. Of those whose nationality is known, a slight majority are foreign nationals. The main places victims of trafficking are exploited are illicit spas and massage parlors, homes (what they call “residence-based commercial sex”), pornography sets, hotels and truck stops.

There are hundreds of illicit massage parlors in Pennsylvania that offer prostitution. The victims are mostly Asian women between 30 and 50, who came to the United States, most legally, to earn money for their families at home, only to find themselves forced or coerced to become modern-day sex slaves. The parlors use the internet to advertise their victims, increasing their criminal business and clientele.

The Human Trafficking Institute reports that illicit massage parlors in America earn $2.8 billion for their owners, and possibly more. The women, who must perform six to ten or more sex acts a day (and frequently live onsite), are treated as “commodities throughout the vast and sophisticated network of IMBs,” being moved between parlors across the country for years. Most incur a debt to get to this country, as much as $50,000, and are forced to work to pay it off — and the debt is continually added to as they’re forced to pay living and other costs as well.

The businesses “operate largely with impunity in American cities,” indeed “thrive in plain sight.” A study of IMBs in Houston, Texas, concluded that “the commercial sex trade is not an aberration within the retail landscape of Houston, but rather a foundational component of that landscape.”

Fighting trafficking in Pennsylvania

We’ve taken steps to address human trafficking in our state. In 2014, the state legislature enacted Act 105 – Pennsylvania’s Anti-Human Trafficking Law. It defined human trafficking to include sex trafficking. The law defines sex trafficking as a first degree felony, “if the person recruits, entices, solicits, patronizes, advertises, harbors, transports, provides, obtains or maintains an individual if the person knows or recklessly disregards that the individual will be subject to sexual servitude.”

“Sexual servitude” covers a wide range of coercive behaviors. Human traffickers can take and keep control of their victims by harming or restraining them or taking their property, or threatening to do so, for example. They can manipulating their documents and abuse the legal process, use debt against them or give them or keep from them addictive substances.

The state has done much for victims. Just last month, legislation authored by my colleague Sen. Cris Dush was signed into law as Act 39 of 2023 to ensure sexually exploited children have access to services by ensuring that the victim would no longer have to identify the “buyer” to obtain necessary services.

The law for adults require that there be proof that the individual wasn’t doing this of their free will. This law states that exploited minors do not need to identify themselves as victims, because many don’t recognize that they’re victims or have been conditioned to believe in harsh retribution against them by their trafficker. This means law enforcement and other first responders can make the determination and get them out of the situation.

More to do

But there’s still so much more to do. We need to study interstate laws to address this within our own borders. We need to advance critical legislation where the perpetrators of trafficking are the ones held accountable, not the victims. We also need to remain vigilant and aware of the problems going on around us. We need to make sure services for victims are adequately funded.

And we need to talk about this.